Located in the Sonoran Desert of southwestern Arizona, the Colorado River Relocation Center, commonly known as Poston, sat on the sovereign lands of the Colorado River Indian Tribes (C.R.I.T.), home to the Pipa Aha Macav, Nüwü, Hopituh Shi-nu-mu, and Diné peoples. The camp was named after Charles D. Poston, the first Superintendent of Indian Affairs in Arizona.

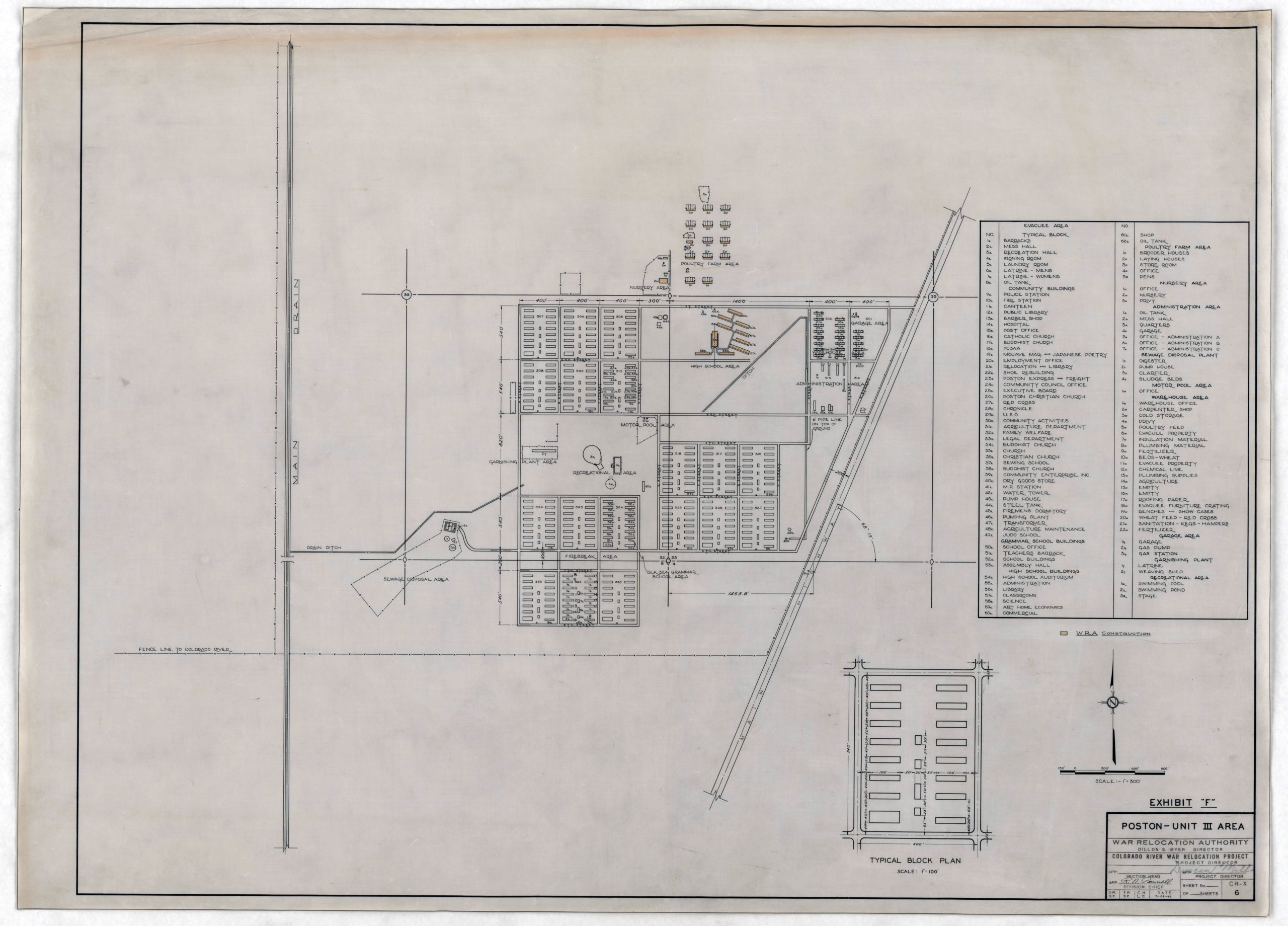

The War Relocation Authority‘s master plot plan for Poston I, II and III. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

Poston was built on 71,000 acres of desert terrain where summer temperatures often soared above 100 degrees Fahrenheit, while winter nights plunged below freezing. When the first incarcerated Japanese Americans arrived in May 1942, they faced incomplete infrastructure—mess halls and hospitals remained unfinished, plumbing was faulty, and refrigeration was nonexistent, leaving perishable food to spoil. The extreme desert heat led to widespread cases of heat stroke, and incarcerees were issued ice, wet towels, and salt pills in an attempt to prevent dehydration.

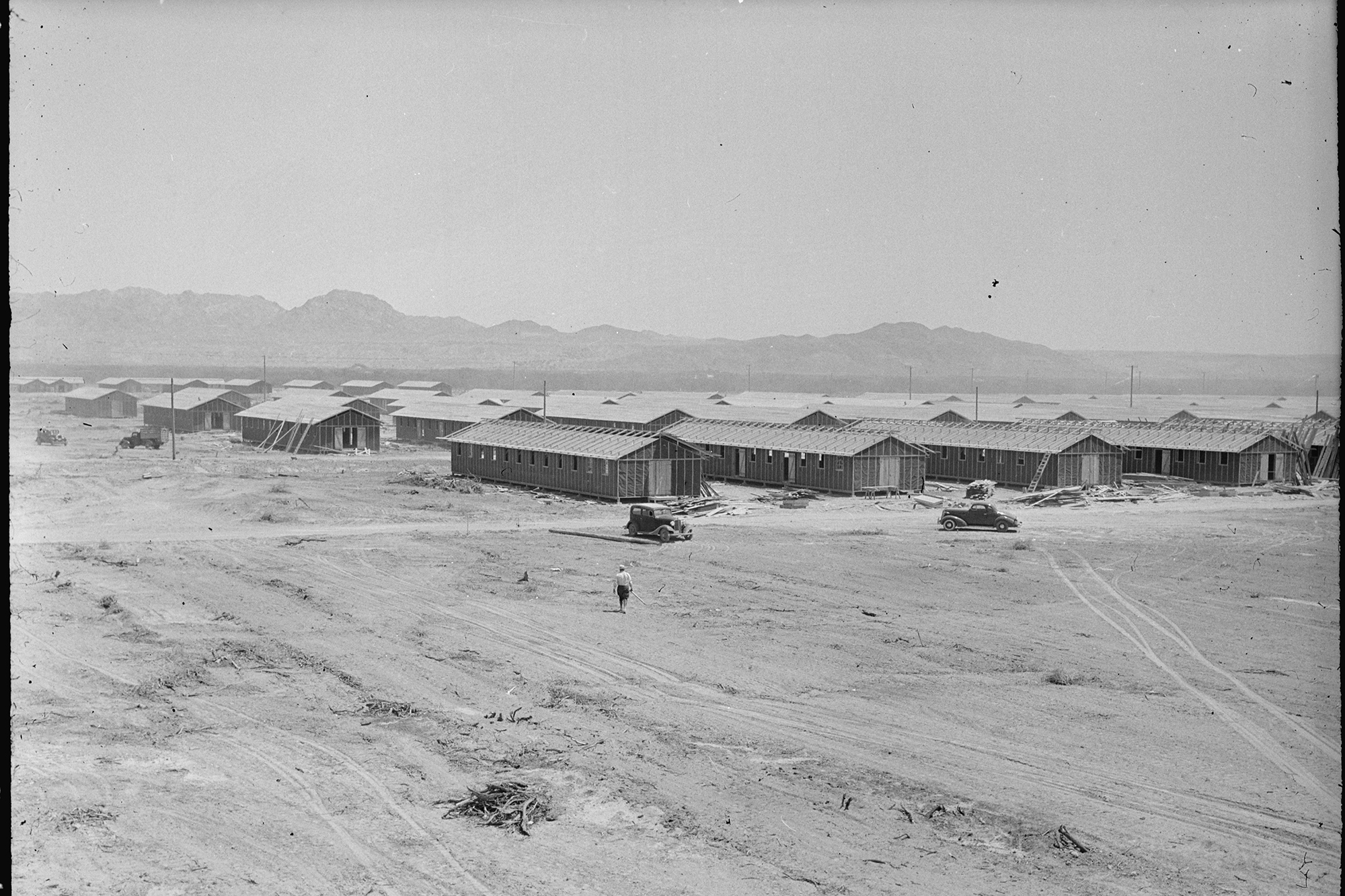

Camp I of the Poston concentration camp. April 24, 1942. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

The Poston concentration camp is located on the Colorado River Indian Tribes Reservation. October 23, 2023.

At its peak, Poston held nearly 18,000 incarcerees, making it the largest War Relocation Authority camp before Tule Lake was converted into a segregation center. It was divided into three separate sections—Poston I, II, and III—which incarcerated Japanese Americans nicknamed “Roasten,” “Toasten,” and “Dustin” in reference to the blistering heat and dusty conditions.

Despite these challenges, incarcerees worked tirelessly to make Poston livable. Using handmade adobe bricks, they built schools, community spaces, and essential facilities. Farmers cultivated vegetable crops, raised livestock, and irrigated the land, making the camp largely self-sufficient.

Many of the original structures at Poston I, II and III have been demolished or fallen into disrepair. Poston I—pictured here—is the largest of the three units and once housed an elementary school, auditorium and gymnasium.

Incarceree students gathered in classrooms at Poston Elementary School—designed and built by incarcerees—to continue their education during their incarceration.

Incarcerees did not passively accept their unjust conditions. Labor strikes erupted in 1942, with adobe workers protesting poor working conditions. When War Relocation Authority administrators barred Issei from serving on elected councils, incarcerees responded by forming an Issei Advisory Board. A week-long protest in November 1942 emerged when two incarcerees were detained without due process, further escalating tensions.

Poston also had the highest number of draft resisters among all War Relocation Authority camps, though resistance was less formally organized compared to the well-documented cases at Heart Mountain.

Aside from “home front” labor like making camouflage nets for the US military, incarcerees constructed buildings, roads and a robust irrigation system that continues to feed into the surrounding farmlands today.

Although they are slowly being restored by grassroots organizations, structures at the Poston concentration camp are vulnerable to decay and arson.

Although Japanese Americans incarcerated at Poston were granted day passes to visit Parker, Arizona, they were largely unwelcome in the surrounding communities. Local businesses refused service, and discriminatory signs such as “Japs, keep out, you rats” were displayed. Even Japanese American veterans in uniform were subjected to racial hostility—one wounded Nisei soldier on crutches was evicted from a store, and another group of Nisei soldiers on furlough was stoned by a local deputy sheriff and his gang.

The Colorado River Indian Tribes opposed the idea of housing a camp on their reservation, but the Office of Indian Affairs and U.S. Army proceeded with the plan in hopes of utilizing incarceree labor to develop the area. Upon the camp’s closing, many of the camp buildings were transferred to the Colorado River Indian Tribes, and some have since been repurposed for use by their community.

Incarcerees at Poston found creative ways to endure the harsh conditions. Some dug underground spaces beneath their barracks to escape the relentless heat, while others planted cottonwood trees to provide much-needed shade. Skilled artisans repurposed scrap lumber to craft furniture, making their barracks feel more like home. Theatrical stages were built to host shibai performances and film screenings, offering moments of cultural connection and escape. Poston also became known for its delicate hand-carved wooden bird pins, a symbol of resilience and artistry that remains an enduring artifact of the incarceration experience.

Why is Poston significant?

The establishment of Poston was deeply controversial within the Colorado River Indian Tribes. The Office of Indian Affairs (OIA) viewed the camp as an opportunity to develop irrigation systems, roads, and infrastructure for the reservation without direct federal funding. However, the Colorado River Indian Tribes Tribal Council objected, refusing to take part in what they saw as a grave injustice against another displaced people. Their protests were ultimately overruled by the OIA and the U.S. Army, and construction proceeded.

When Poston closed on November 28, 1945, its buildings and infrastructure were transferred to the Colorado River Indian Tribes. However, financial compensation promised by the War Relocation Authority never fully materialized—the agreed-upon rental fees were largely offset by deductions for land improvements.

Despite this fraught history, the Colorado River Indian Tribes have worked closely with the Japanese American community to preserve Poston’s legacy. Survivors and descendants continue to return for annual pilgrimages, ensuring that the injustices of incarceration are not forgotten.

Please note: The photographs on this page were taken with written permission from the Colorado River Indian Tribes. This site is located on the sovereign lands of the Colorado River Indian Tribes, and access is subject to the jurisdiction and authority of the Tribal Government. All visitors must obtain prior written permission from the Colorado River Indian Tribes before entering. Unauthorized access is strictly prohibited.

This historical overview is informed by research from the Densho Encyclopedia (accessed in 2023), National Park Service (accessed in 2023), and interviews conducted during a visit to the camp in 2023.